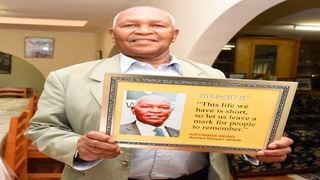

Legendary Kenyan athlete Kipchoge Keino during an interview at his Kazi Mingi home in Eldoret, Uasin Gishu County on September 14, 2021.

| Jared Nyataya | Nation Media GroupWeekend

Premium

Uhuru 58 and a book about Kenya’s great sporting history

What you need to know:

- National independence days are good instances of such occasions for reflection, appreciation and resolution.

- Even back in the colonial times, heroes like footballers Joe Kadenge and Oliver Lidonde had emerged on the sporting scene.

“Those who know not whence they come,” I wrote in 2019, “know not wither they go.” As I put it in my original Kiswahili, “Asojua atokako, wa’aendapo hajui.” I wrote the line in homage to our greatest history teacher, Prof Bethwell Alan Ogot, on his 90th birthday.

The sentiment could, however, be extended to all celebrations of our history, like personal or institutional anniversaries, national days or even the big spiritual festivals. Marking such memorials affords us the opportunity to reflect on our beginnings, the journeys we have travelled, the stages we have reached and the destinations towards which we aspire.

National independence days, like Kenya’s Jamhuri Day, due tomorrow, or Tanzania’s Uhuru Day, marked last Thursday, are good instances of such occasions for reflection, appreciation and resolution.

Thinking of Kenya’s 58th independence anniversary, for example, I focused on the impression that our sportsmen and sportswomen are, arguably, our sweetest “matunda ya uhuru” (fruits of independence).

Using the three criteria of self-sacrifice, unshakeable discipline and solid demonstrable performance, I feel that our sportspeople have brought Kenya more glory and recognition than any other cadre of performers has in our national effort. This is why I pray and urge that the whole history of Kenyan sport be told in a major coherent and comprehensive work.

As I keep boasting, I have been there since the dawn of East Africa’s independence history. Of Tanzania’s great moment, 60 years ago, I remember not only Mwalimu’s clarion call of “uhuru na kazi” (freedom and work) but also his exceptionally generous (but sadly ignored) offer to delay Tanganyika’s independence till Kenya and Uganda were ready to join her (Tanganyika) in an East African Federation.

record-shattering careers

Kenya’s first night of uhuru, which I followed on shortwave radio, sticks in the memory because of the wananchi’s unqualified and joyful optimism, projected in the iconic lyrics, “jogoo limewika, usiku umekucha, taabu zimeisha, Afrika ni yetu” (the rooster has crowed, the night is over, our troubles have ended, Africa is ours).

In Kampala in 1962, as I might have told you, I was among the massed choir that sang the “Oh Uganda” national anthem for the first time on October 9, under the direction of its composer, the late George Kakoma, who was later briefly my colleague at KU.

They were heady and exciting times, those, and their poignancy has not completely worn off, despite the flight of the years and the recurrent waves of disillusionment. The one streak of East African activity of which I have been consistently proud remains our sport.

During the dim days of Idi Amin, for example, John Akii-Bua went and earned Uganda’s first-ever Olympic gold medal, in the 400-metre steeplechase at the Munich 1972 Games. Do you remember Tanzanian Filbert Bayi Sanka, who set a 1500-metre world record in 1974 and did the same for the mile in 1975?

Even back in the colonial times, heroes like footballers Joe Kadenge and Oliver Lidonde had emerged on the sporting scene. You probably know that Okot p’Bitek earned his first trip to England as a footballer, eventually staying on to pursue higher studies at Aberystwyth and Oxford.

I have never been more than an average club sportsman. Still, the joy, pride and inspiration I have derived from sport, especially Kenyan sport, remains a precious and treasured part of my biography. I remember, for example, an uplifting visit that Kipchoge Keino and his star colleagues paid us at Antananarivo during our student days in Madagascar in 1967.

Kip and several of his colleagues, who were at the height of their record-shattering careers then, were probably on an official cultural exchange mission to Madagascar. But they called on us at the university and we were all justifiably proud to identify ourselves as Kenyan. That included me, a Ugandan, who had come from the University of Dar es Salaam!

The little I remember of our face-to-face with Kip Keino is of his humble and relaxed demeanour. Maybe my image of a world-beating champion had been of a haughty and imperious character who would receive our avid admiration with a cool reserve at the best. Kip was nothing like that, and he smiled, laughed and joked freely with us.

1987 All Africa Games

Our pride reached its peak when Kip and his colleagues staged an exhibition meet at the Antananarivo National Stadium, and the announcer’s amplified voice floated over the grounds, introducing one “recordman du monde” (world champion) after another.

It was only sport (michezo tu), but the joy, pride and identity boost that these athletes’ appearance gave to our young hearts still radiates through my rattling bones down to this day. I have not kept in touch with my Kenyan Madagascar contemporaries, but I am sure many of them would remember this event with relish.

My other high with Kenyan sport was the Nairobi 1987 All Africa Games, where I was accredited as one of the official reporters on the Lawn Tennis event at the Nairobi Club. I did not, for some reason, get my official uniform, despite the organises’ elaborately taking my measurements for it, but I had the rare opportunity not only to watch the continent’s top players in action but also to interact close up with them in interviews and conversations.

These included greats like Zimbabwean Cilla Black and her brother Byron, who were later to feature in international tournaments, like Wimbledon. It was also a joy to watch our best players of the day measuring their skills against the continental giants of the sport.

Anyway, the point is that celebrating Kenya’s and East Africa’s history should include a prominent celebration of our sport and its principal actors. A good start towards that celebration should be an accurate, articulate and attractive narrative of our principal actors in the sports sector. Their selfless, disciplined and dedicated performance is a worthy model of patriotic commitment for all of us.

Happy and sporty Jamhuri Day to you all.

Prof Bukenya is a leading East African scholar of English and literature. [email protected]