Tigritude and the significance of a Black History Month for Africa

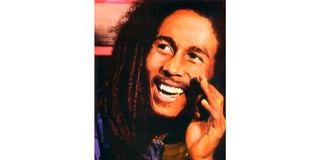

Legendary Jamaican reggae icon the late Bob Marley. February, the short febrile month in which Bob Marley, Rosa Parks and I were born, will be upon us next week.

February, the short febrile month in which Bob Marley, Rosa Parks and I were born, will be upon us next week. This whole month is observed as Black History Month in the US and Canada and several other countries with significant Black Diaspora communities.

The activities of the month remind the world of these communities’ long and difficult struggle for self-realisation, celebrate their achievements and explore prospects for their betterment.

Anyone with an inkling of the troubles and tribulations that Black people have suffered and still suffer in the Western World needs no explanation of the importance of their reminiscing, reviewing and resolving their experiences and aspirations.

This has become even more urgent in the face of an aggressive move by the descendants of those who committed crimes of cosmic proportions against Black people to suppress the truth about those nefarious abominations. The teaching of Black history, for example, is currently a matter of court cases in some Western countries.

Today, however, I would like us to direct the concept of Black History squarely on Africa. Many of us on this continent, which is overwhelmingly Black, probably take this fact for granted. We see no reason why anyone should make a song and dance about our Blackness. “We’re black,” most of us might say. “So what?” By way of answering this, let us start first recall the famous exchanges about the matter between two giants of African Literature, Leopold Senghor and Wole Soyinka.

“The tiger does not declare its tigritude because the tiger is an animal.” That is how the late Leopold Sedar Senghor, first President of Senegal and principal founder of the Negritude (Blackness) cultural and literary movement, replied to Wole Soyinka’s famous pronouncement, “A tiger does not declare its tigritude. It pounces on its prey and devours it.” Soyinka’s snide remark was a criticism of the (mostly Francophone) negritude writers’ apparent overconcentration on the obvious fact of their blackness.

In his witty reply to Soyinka, Senghor suggests that we should not be compared to animals, which supposedly have no power of reflection. In any case, Senghor goes on to say, whether an animal, say a zebra, is aware of its stripes or not, it does not change the fact that it has the stripes and they are used as a way of recognising it. Whether Black people acknowledge their identity or not, it does not change the fact that their colour has been used to identify them and often, unfortunately, to victimise them.

Many observers, back in the 1960s, saw the repartee between Senghor and Soyinka as a polemic marking a contrast between Anglophone pragmatism and Francophone romanticism. To me, however, the contrast signifies more of a generational and historical shift rather than a culture-linguistic clash. Senghor’s Negritude, which Soyinka was humorously bashing, arose in the late 1930s, growing through the 1940s and early 50s when Black African liberation from colonialism was still considered remote.

Soyinka, on the other hand, came into his own mostly in the 1960s, when several African countries had already attained or were attaining their independence. He could, therefore, afford to take for granted the concepts and aspirations of Negritude (blackness) and unfettered African reality that were distant dreams to Senghor and his contemporaries at the height of colonial exploitation, including the Africans’ being dragged into two “World Wars” (1914-18 and 1939-45) in which they had absolutely no stake.

Incidentally, Soyinka made his “tigritude” comments during the historic “Conference of African Writers of English Expression”, held at Makerere in June 1962. Young people often ask me if I attended this indaba. I could have, since I was only 20 kilometres outside Kampala at the time. But I still had to do my Cambridge “O-levels” later that year and “A-levels” two years later. So, I did not attend. But it is nice being mistaken for one of the greats.

Living long is seeing a lot (kuishi kwingi ni kuona mengi). A Nairobi cab driver once even asked me if I played golf with Hayati Mwai Kibaki at Makerere. I had to explain that Hayati did not play golf in his Makerere days. Moreover, I only joined Makerere in 1978, seventeen years after the great man resigned from his lectureship there to join Kenyan politics in 1961.

Let us, however, return to Soyinka and the confidence that prompted him to suggest that there was no need to obsess about African/Black identity. Can we, Africans of the post-independent generations, honestly say, that we need not reflect on our identity, our aspirations, and what we have made of our continent since we gained Uhuru (independence) in the 1960s and the years thereafter? Toundi, a character in Ferdinand Oyono’s novel, Une Vie du Boy (Houseboy), which has negritude leanings, asks the narrator, “Brother, what are we black men who are called French?” What would you say if I asked you today, “Dada, kaka (sister, brother), what are we Africans who are called independent?”

We have denizens of autocrats, military dictators, and corrupt predatory administrators on our continent. Their deeds, like impoverishing wananchi, suppressing human rights, degrading and destroying our environment and provoking internal and interstate conflicts, deeds that render our countries “unloved and unlovable”, as Denis Brutus put it.

Can we truthfully avoid the necessity of reflecting, again, on what we, “independent” Africans are, and “where the rain began to beat us”, as Achebe renders the Igbo saying? If we do not humbly go back to the roots of our existence as an African community, reflect creatively on our “Ubuntu” (humanity and humaneness), we may never be able to avoid being drenched in the rain.

Maybe, finally, what we need is a Month of African History of our own, to evaluate the journeys we have travelled and map out the new routes we shout take to our full self-realisation as individuals and as a continent. My feeling is that we need both the Senghorian negritude reflectiveness and the Soyinkan tigritude activism.

Prof Bukenya is a leading East African scholar of English and [email protected]