Expensive books? We only have ourselves to blame

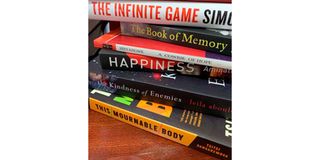

A pile of books.

On page 3 of last week’s edition of the Sunday Nation was an article by Nyambega Gisesa reporting that author and magistrate Alice Macharia can barely afford her own book. The author baulked at the Sh18,000 price tag for a book she researched and wrote.

That the publishers were charging her in dollars or pounds appeared lost in the story – the Kenya shilling is a very weak cousin of the two. My first reaction was: so what if the book costs that much? Anyone who really loves books – or rather, someone who is interested in the book – would buy it regardless of the price. Right?

Maybe, maybe not. But we do love the European standard, especially the British quality, right? We take our children to expensive schools that suggest that they are built near some brook or are academies, and teach the IGCSE at ‘O’ and ‘A’ levels with the promise that the children will get ‘international’ quality education that in future will make them global citizens. Right?

We would uncritically buy expensive clothes, vehicles, household items, food or even drinks simply because they have that mark of foreignness – what is alien is superior and preferable to the local.

Well, some Africanist scholars and cultural activists have claimed that we love the foreign standards because we are still colonised mentally. This claim could be true but it is in itself the very sign of the power of colonialism and neocolonialism. It is much easier to speak of colonialism and decolonisation than it is to resolve the conundrum.

How ironic is it that most critics of colonialism and neocolonialism live, work and are beneficiaries of the very systems that established and managed the colonial enterprise, but which have simply changed their form but hardly the content? Why do Africans continue to publish books in Europe, Asia and America? Why can’t Africans publish books in Africa?

New stories

Maybe the real question should be: what are books? Is a book the content or the content and the form? Whichever way one looks at it, a book is simply a conversation or an encounter between two people: the author/speaker/performer and the listener/audience.

But because we can’t have the same author in two places or more at the same time, the book is the medium by which that author addresses different people in different places at different times, sometimes for different reasons. The book is a magic wand that generates readers or listeners and provokes conversations, and sometimes produces new ideas leading to new stories and other books.

So, books are really just an idea or ideas captured in that form that the Johannes Gutenberg bequeathed the world. Gutenberg’s invention revolutionised the world in many ways – literacy spread, ideas circulated beyond their points of origin, other inventions became possible because individuals could read about experiments elsewhere etc.

It is therefore surprising that Africans, or should we just say, Kenyans, are yet to decolonize themselves of the hazards of having their ideas printed, stored, distributed and sold (from) elsewhere. It is expensive to publish a book. It costs money to research, write, edit, design, print and sell a book. It costs more if the book has to be shipped from abroad. If you add taxes, then books become too expensive for the common reader.

It, therefore, follows that Rights of the Child, Mothers and Sentencing: The Case of Kenya by Alice Macharia could actually cost what was quoted. After all the cost is also determined by the socio-economic conditions in which the book is published. For a book published in Europe, America and parts of Asia, often academic institutions and national libraries have budgets to buy such books. Some non-academic organisations also have adequate funding for their research libraries.

This is about economic power translating into hierarchies of intellectual difference. The irony here being that very local (Kenyan) ideas are affordable to foreign audiences while they are too expensive or unaffordable locally.

To ‘decolonise’ this situation of intellectual inequity – and without blaming foreigners – we need to rethink our own relationship with our world. Why do we research local conditions? Why do we write about Kenya or Africa? Why do we publish books or shoot films/documentaries?

What are local archives for? If one goes to North Horr or Lambwe Valley to research on, say, ‘gender imbalances in primary school registration and completion’, why would such research be published in Europe or Asia or America, and be completely unreachable or unaffordable to an individual in North Horr or Lambwe Valley?

Non-academic writers

Kenyans (or say Africans) need to perpetually remember that local ken needs to serve locals first before it is shared with the rest of the world. Our governments – both national and county – need to think creatively and invest in the publishing sector. At independence, the government put money into publishing.

Today we still have Jomo Kenyatta Foundation – an educational publisher set up in 1966. Then there is the Kenya Literature Bureau – another State-owned publisher established in 1947. Even the Kenya Institute of Curriculum Development is a publisher.

What are they doing for local non-academic writers? Public universities have in the past been publishers, although, unfortunately, some of them have either discontinued their presses or cut down on printing. How can this happen in institutions whose core mandate is to generate and disseminate ideas? What university worth its name would kill its publishing unit?

We shouldn’t blame foreign publishing companies for the high cost of books if we can’t deliberately fund and support local publishing companies and programmes. The government has just to support Kenyan publishers in one form or another. It should withdraw the VAT on locally-produced books. It should give tax breaks to publishers when they import printing machinery. It should fund initiatives such as the now inactive National Book Development Council of Kenya.

It should support the incipient e-book sector by funding purchase of some copyrights from foreign publishers as well as e-archiving of local books. ‘Buy Kenyan, build Kenya’ should also mean the government support for writers, publishers, sellers and buyers of books in Kenya.