End of an era in Caribbean writing in Lamming’s death

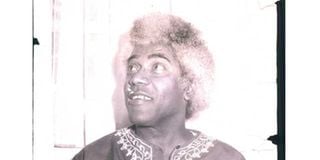

George Lamming, author of the biographical novel ‘In the Castle of my Skin’ shortly after completing a lecture tour at the Universities of Nairobi and Dar es Salaam in 1975. He died last Saturday in Barbados aged 94.

George William Lamming, author of In the Castle of My Skin, the definitive novel of Caribbean literature, died last Saturday, aged 94.

His death, which provoked reverential eulogies across the world, was practically the last of a generation of black writers from the Caribbean Islands who theorised in essays and fiction the pains and pleasures of being Black islanders in the Caribbean towards the end of colonialism and after.

Lamming’s writings demonstrate the essential meaning of blackness that had survived the separation, exploitation, dispossession, and marginalisation of descendants of slavery and survivors of colonialism in the Caribbean Islands.

In fact, it is difficult to think about Caribbean literature without reserving a space for Lamming and In the Castle of My Skin, which I first encountered at Moi University in the late 1990s, where professors Busolo Wegesa, CJ Odhiambo and Peter Simatei had placed it as a core text in teaching life and society in the West Indies.

Later, I would use my passion for Lamming’s writing to extend my interest in the nexus between race and minority literatures, which then enabled me to discover new vistas in post-colonial, area studies, minority, and diasporic literatures.

While all such writings impacted on my thoughts about the discipline, I have always gone back to In the Castle of Skin as my touchstone text whenever I want to gauge a given author’s understanding and expression of what may vaguely be described as the contemporary Caribbean condition.

The novel’s greatest success is in how it illuminates the futile colonial scheme of numbing Caribbean people’s sensibility to their historical, cultural, and material worlds; how colonial logic required total subservience from the islanders while giving them so little in return.

This way, the novel, dubbed “the fundamental book of a civilisation” by a New Statesman reviewer, remains an important tour de force of easily one of the leading intellectuals of the 20th Century Caribbean Islands and the Black world.

Because of its positioning as a pioneer in the problematisation of the predicament of material precarity and racial blackness in a capital ridden world of presumed Caucasian privilege, In the Castle provided a mirror for critical self-appraisal of a then bubbling black consciousness at a time when the drive for freedom, in the widest possible sense, was the rage in the colonized worlds.

In critical ways, Lamming’s most famous novel foreshadowed some of the most topical concerns in the current intellectual thought patterns; ecocriticism, decoloniality, and the more established concern with the meaning of global blackness; all of which coalesce around post-colonial literatures, narratives of the Black Atlantic and, more recently, scholarship on critical race theories.

Perhaps because of all these, and perhaps because of Lamming’s framing of the Caribbean experiences in ways that preceded and even eluded other Caribbean men of letters such as Naipaul and Walcott, In the Castle has dominated reading lists of courses on Caribbean life and society since 1953, when the novel first appeared.

In the Castle of My Skin is a novel of childhood, of a troubled adolescence and of immense loss, set in Barbados that was still scarred by the traumas of slavery and British colonialism; peopled by a community on the fringes of material conveniences, yet one that perceived its own earthly sphere as ‘little England’ – a salute to the evil genius of British colonialism that branded illusions of Englishness on its alienated survivors.

In the novel, the initial contentment and basic struggles against nature for routine survival, soon gives way to a greater political awareness and revolt against the colonial order, which in turn yields to an emerging local elite, but it is a slimy elite driven by greed and selfishness that disillusions the majority of low class members who expected more and better.

In the Castle of My Skin, from the author’s discerning genius contrasted with the despicable conduct of the political class that he rebukes, spoke to Frantz Fanon’s 1961 observation, in The Wretched of the Earth, that “each generation must, out of relative obscurity, discover its mission, fulfill it, or betray it.”

Doubtless, Lamming emerged from obscurity to fulfil his mission as a leading thought leader way beyond Barbados where, according to the Barbadian Prime Minister, Lamming “stood for decades at the apex of our island’s pantheon of writers.”

Born in 1927 in Barbados, an island East of the Caribbean, Lamming influenced generations of thinkers across the world through his writings, radio discussions, and university teaching with stints at universities of West Indies Mona, Jamaica, Texas, Pennsylvania, and Brown. He also lectured in universities in Denmark, Australia and, closer home, Tanzania.

In his ten books – six novels and four non-fiction works – Lamming explored the impact of colonialism on the making of black identities and their corresponding cultures.

Water with Berries, first published in 1971, is a political allegory of William Shakespeare’s The Tempest, which dramatises the material basis of the construction of race as the organizing principle in accessing power and other resources.

It could well have been this concern that, apart from sowing the seeds of area studies or postcolonial discourses, whichever label you fancy, initiated connections of racial solidarity among conscientious 20th Century intellectuals of a global presence, such as Ngugi wa Thiong’o.

In fact, two of Ngugi’s essays in Homecoming (1972) establish a shared link of struggles that black people of the Caribbean Islands have with their compatriots in continental (East) Africa, especially the push against a colonial order that privileges whiteness.

In Ngugi’s view, Lamming acutely understood and captured how colonial education connived with its bureaucracy and a variant of Christian doctrinaire to lull the villagers into a servile acquiescence to the colonizer’s whims.

It is the same plight that awaits the deprived, both in Creighton Village of Lamming and Kenya with which Ngugi draws parallels – the poor survive colonialism, only to be exploited and dispossessed by an emerging local elite.

Lamming pursued these themes of post-independence disillusionment in Of Age and Innocence (1958), and of the navel ties between Caribbean Islands and Africa in Season of Adventure (1960).

Even The Pleasures of Exile (1960), in its exploration of how individual, political and cultural identities are overdetermined by colonialism and its legacies, also resonated with Edward Said’s widely cited essay entitled “Reflections on Exile.”

For Said, another ambassador of the marginalized voices, “exile is strangely compelling to think about but terrible to experience. It is the unhealable rift forced between a human being and a native place, between the self and its true home: its essential sadness can never be surmounted.”

These are the concerns, from the standpoint of the Caribbean Islands, that Lamming illuminated largely remained the same – trapped in a vicious cycle of global capital and neoliberal dominance.

The tragedy is that some symbolic darkness continues to engulf such transformative thinkers like Lamming, whom, in the end, goes in a manner similar his narrator in In the Castle of My Skin: “The earth where I walked was a marvel of blackness and I knew in a sense more deep than simple departure I had said farewell, farewell to the land.”

The writer teaches at the University of Nairobi