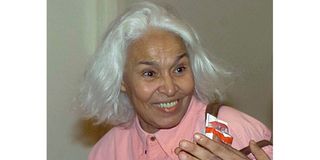

Daughter of the Nile: Tribute to author Nawal El Saadawi

Egyptian author and activist Nawal Saadawi.

What you need to know:

- Her life and literary works have been consistent in fighting against oppression.

In many ways, writing is… an aggressive, even a hostile act. You can disguise its aggressiveness all you want with veils of subordinate clauses and qualifiers and tentative subjunctives, with ellipses and evasions—with the whole manner of intimating rather than claiming, of alluding rather than stating—but there’s no getting around the fact that setting words on paper is the tactic of a secret bully, an invasion, an imposition of the writer’s sensibility on the reader’s most private space”.

These words by Joan Didion aptly describe the writing of Nawal El Saadawi, the world-famous Egyptian writer who died on March 21, 2021 at the age of 89. Saadawi was a dissident writer who was a firebrand and didn’t hide it. In her first autobiography, A Daughter of Isis, she recalls her outrage when she began to realise that, in Egypt, daughters were not considered equal to sons.

When her grandmother told her, “a boy is worth 15 girls at least …Girls are a blight,” she stamped her foot in fury. And that was the early signal of the birth of a hardcore feminist.

Born in 1931 in Kafr Tahlah, an Egyptian village by the Nile, her life and literary works have been consistent in fighting against oppression. For this, Saadawi was “pilloried, censored, imprisoned and exiled for her refusal to accept the oppression imposed on women by gender and class”. However, she trudged on and became an internationally renowned feminist writer and activist.

She was the founder and president of the Arab Women’s Solidarity Association and co-founder of the Arab Association for Human Rights. Like many other writers, Saadawi was restless and aggressively rattled the status quo. Most writers are harassed by their creative spirits on one side and society’s rigid norms on the other.

Blasphemy

Many of them have been misunderstood, rebuked and even accused of blasphemy. James Joyce was “censored by everyone until they decided he was a genius”. For Salman Rushdie, “Everyone is still trying to kill him for apostasy”. D.H. Lawrence was banned by England for throwing Victorian taboos out through the window.

Our own Ngugi wa Thiong’o stirred up the hornet’s nest with his play, Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want) and he was incarcerated for it. On her part, Nawal el Saadawi led a literary coup against Egypt’s heavy-handed patriarchal society. She wrote not only about pastoral swoonings and picaresque adventures but also about the brutal reality of living in an oppressive society.

Taking on the tyrannical Egyptian patriarchy, she wrote, in suppressed panic, the fictitious Memoirs of a Woman Doctor in which a young Egyptian woman chooses a career in medicine and clashes with traditional family norms for it.

The young woman also refuses to accept an arranged marriage and fiercely fights for her independence to make her own choices touching on her life and dreams.

She contrasts her life and her brother’s when she says, “My brother went out into the street to play without asking my parents’ permission and came back whenever he liked, while I could only go out if and when they let me.

My brother took a bigger piece of meat than me, gobbled it up and drank his soup noisily and my mother never said a word. But I was different: I was a girl. I had to watch every movement I made, hide my longing for the food, eat slowly and drink my soup without a sound”. She paints a picture of how it feels to be a girl in an unabashed patriarchal society. Saadawi writes with a detachment that breaks the heart.

Cheerless place

She wrote over 55 books and one of her most popular novels is Woman at Point Zero (1973), a fictional account inspired by the true story of a woman she met at an Egyptian prison before her execution. It’s a poignant novel exploring “the themes of women and their place within a patriarchal society”.

The novel leads to a rancid, cheerless place (the death of the woman)—a brutal but apt metaphor showing that Saadawi was done rhapsodizing about an ideal Egypt. She had to make do with reality; and it was messy. It, therefore, had to be written that way; warts and all.

Some of her other books include The Absent One (1969), Two Women in One (1971), The Death of the Only Man on Earth (1975), The Children's Circling Song (1976), The Fall of the Imam (1987) and Ganat and the Devil (1991).

Saadawi was definitely a force for good and justice. Unfortunately, all good things come to an end.

As Mark Twain once said, “Homer’s dead, Shakespeare’s dead, and I myself am not feeling at all well.” This reminds us that we are all sojourners on earth, just like all our forebears have been and, at an appointed time, we must ‘un-pitch’ our tents for our celestial flight; never to return. Saadawi has unpitched her tent for her flight but, fortunately, her works are still with us.