Africans, the ecopoetics of the tree and return of the book fair

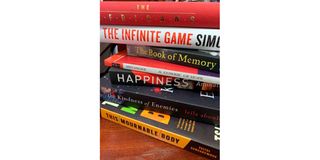

Keep an eye out for books and other materials that focus on the environment, especially on trees.

What you need to know:

- Immerse yourself in the refreshing streams of the recorded and inscribed creativity of the Fair and the Festival.

- Make and renew friendships with the most incisive minds and most expressive tongues and pens of our Continent and our Diaspora.

- Keep an eye out for books and other materials that focus on the environment, especially on trees.

The Nairobi International Book Fair is in full swing as you read this. I would have loved to be in Nairobi to share with you this hallowed celebration of the book and all of us who love it, write it, edit it, publish it, distribute it and read it.

But alas, fate decreed that I will not arrive in time for it, or for the concomitant and promisingly inspiring Macondo Literary Festival. Please represent me at both.

Immerse yourself in the refreshing streams of the recorded and inscribed creativity of the Fair and the Festival.

Make and renew friendships with the most incisive minds and most expressive tongues and pens of our Continent and our Diaspora.

This is what we have been doing around this time of year for the better part of a quarter century.

For me, however, do one special little thing as you enjoy the extravaganza.

Keep an eye out for books and other materials that focus on the environment, especially on trees.

In the creative, literary field, this is what we call ecopoetics. Ecopoetics suggests the simple concept and experience of a relationship between the environment (ecology) and poetry or literature in general.

As with all literary concepts, ecopoetics suggests both a phenomenon and a theoretical approach. The phenomenon here is “ecocreativity”, the actual production of works of literature that shows a strong awareness of and concern for the environment.

Voice of the People, a play by my friend and our new Busia Senator, Okiya Omtatah Okoiti, and Ng’anga Mbugua’s Terrorists of the Aberdares, featuring an elephant called Kanywaji, are good examples of explicit environmental awareness in creative work.

I have told you of my own play, A Hole in the Sky, which, like Alex Nderitu’s play, The Talking of Trees, is largely inspired by the late Wangari Maathai, the woman who loved trees to extremes.

Environmental awareness

All of these have been analysed and discussed by literary scholars and critics who highlight environmental awareness in them.

One of these eminent critics is my former Makerere student, Dr Eva Nabulya, and now a don there, who worked on ecocriticism for her PhD at Stellenbosch.

Indeed, ecocriticism is the second, theoretical, aspect of ecopoetics. It uses ecological or environmental awareness to interpret literary works.

Its emergence as a major literary theory and practice reflects our universal growing concern for the environment and its impact on our development and even survival as a species.

These are the thoughts swirling around my mind as I contemplate trees.

“Poems are made by fools like me, but only God can make a tree.” These are the two concluding lines of Joyce Kilner’s poem, “Tree”. This Joyce poet is a man, as, in the Irish-Gaelic tradition, from which I believe Kilner descends, “Joyce” is unisex. Another male bearer of the name, for example, is Joyce Carey, a colonial administrator in West Africa, whose grotesquely facetious stories of Africa provoked Chinua Achebe into “telling our own story”.

Trees, however, and poetry are our focus today. From time immemorial, great works of literature have been composed about or around “nature”.

This includes the sky and its lights, clouds, rainbows and thunderclaps, the earth and its mountains, valleys, oceans, seas, lakes, rivers and deserts, and the teeming life of flora and fauna around us.

Of all the phenomena in nature, however, the tree, whether in its single state or in its collectives of coppices, woods or forests, seems to dominate the human imagination.

Food source

This should not be particularly surprising, considering our dependence on trees through the aeons of our evolution. Trees have been our sources of food as far back as our memories stretch.

They have also provided refuge and shelter to us in both their raw and processed forms.

Clothing also came from trees for many African people, like the Waganda, who beat lubugo cloth out of the barks of some varieties of fig trees.

Earlier textile technology of course included the proverbial fig leaf. The earliest vehicles for most of us seaside, lakeside and riverside dwellers were hollowed-out tree trunks, the mtumbwi, which survives in pretty much its primaeval form to the present day. The litany of the benefits of the tree are truly endless.

Maybe we should add one more crucial benefit of trees to our acutely health-conscious age, medicines.

From root through bark and stem to leaf, fruit and seed, the tree is our primary dispensary.

Even with all the boasts and posturing of “modern” synthetic formulae, the plant and, especially the tree, remains our main pharmaceutical resource, especially for us in Africa.

Equally importantly, trees have psychotherapeutic properties. In other words, they help to treat the mind. We learn that a walk among trees, with a gentle touch and even a hug of their trunks, has a calming and relaxing effect on our feelings and emotions.

Little wonder, then, that as the concrete jungle eats up our erstwhile tree-greened environs, we are haunted by the spectre of permanent collective restlessness, bad temper and violence.

How many kilometres do you have to drive to get to the Park, Arboretum or Botanical Gardens nearest to you?

Do you, in any case, bother to take the free dose available to you and your people?

Do those of us with open spaces remember not to destroy the trees on them or “if you cut down one, plant two and tend them”?

Woe betide us if our eyes are fixed only on the number of apartment blocks we can plant on our plots!

After you give me your feedback on what you observe of the ecopoetics at the Book Fair, I will lead you into a chat about the social and spiritual role of the tree in our lives.

It will be a joy sitting under the “palaver tree” in the middle of the settlement and chatting about all the saving graces of our branched brown and green relatives.

Meanwhile, who would care for a book that does not mention a tree?

Prof Bukenya is a leading East African scholar of English and [email protected]