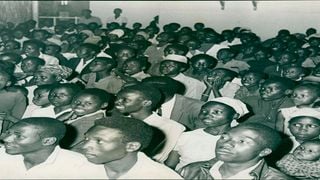

Christmas celebrations at the Bahati Social Hall, Nairobi in 1969.

| File | Nation Media GroupKenya@60

Premium

Why Kenyans look nothing like they did 60 years ago

Six decades later, Kenyans look nothing like they did at independence. What we eat, how we speak and style ourselves have evolved over the years. As modernity and new trends permeate our culture, our sense of fashion has changed significantly. Interestingly, even our deportment has undergone an evolution, changing our posture and gait.

But how differently did we look 60 years ago?

Few things define us quite like fashion does. In Kenya today, muscular, heavy-bearded men in chino pants carry tote bags while bald women walk in ripped jeans and impossibly high heels. Both sexes wear androgynous outfits freely. Whether quirky, audacious or outright flirtatious, if it is wearable, Kenyans will rock it.

Like in other world societies, the evolution of life in Kenya can be measured in terms of the evolution in fashion, with seasons, pop culture and other sociocultural trends influencing how we dress. At independence, Kenyan men typically wore short, well-combed hair, dressed in a shirt, a pair of pressed trousers and a jacket.

Women wore skirts and buttoned-up blouses and low-heeled shoes.

Over the years, however, the line between what men and women wear has grown blurrier, and so has fashion inspiration from elsewhere in the world become the way of life in Kenya. This has given rise to brands such as KikoRomeo, which makes loose fittings for both sexes. “We make the same pieces for men and women with only slight alterations while maintaining our style,” explains Anne McCreath, the proprietor, who also wears ‘‘mannish and arty’’ outfits.

When it comes to hair, Kenyans wear theirs in all manner of stylish, bold and even eccentric ways. Other hairdos inspire nostalgia for years gone by. At independence, short hair worn with minimal accessories was the most popular hairdo among the Kenyan womenfolk, for grace and elegance. Only oil was used to keep it in shape.

Fashion comeback

Some of these earlier styles have been making a comeback after being retrieved from the shelves of history. Women like Karen Wairimu wear natural, short hair that is considered easier and less expensive to maintain. ‘‘The first time I cut my hair three years ago, I felt I looked good in it. So I kept it short. It is more convenient and much cheaper than going to the salon. I do not like sitting still for hours to have my hair done. It is exhausting,’’ Wairimu says and adds that she also fears getting her hair frayed.

These days, Kenyan men wear ponytails, cornrows and dreadlocks. Writer and blogger Eddy Ashioya sports a thick mass of dreadlocks that he wears under a baseball cap. Ashioya says it enhances his identity and sense of freedom. ‘‘I simply like long hair. On a deeper level, this is a silent protest against any sort of confinement. I hate being told what to do, especially how to style myself,’’ says the writer.

Today, the average Kenyan is more tattooed than 60 years ago as global influences on fashion and self-image infiltrate our culture. Ronnie Ndung’u, for instance, has on his arms, legs, neck and back a network of as many as 15 tattoos that he proudly displays to whoever cares to look. ‘‘I feel comfortable in my skin,’’ he says giggly, stroking the stud on his left ear.

Revellers at the Kenyatta International Convention Centre on March 4, 2023, during the Shoke Shoke festival.

Then there are those like Esther Chebet, 21, who go further to enhance their looks. The design student carries a substantial amount of metal on her body, with piercings on virtually every visible tissue and lobe. She has a nose ring, a tongue piercing, eyebrow piercings and more jewellery on her lower lip, both ears, breast and navel.

’’The piercings have nothing to do with my sexual orientation or extreme beliefs. It is a way of expressing my sexuality as a young woman,’’ Chebet explains.

Multilingual

With 44 official tribes, Kenya is considered multilingual. More than 65 languages are spoken in Kenya. It was different at Independence, with the majority of Kenyans speaking only their native language and some Kiswahili. Still, some spoke one language. Those who had an education could also speak English. Today, some Kenyans like Maryanne Kerubo converse in as many as five languages with ease.

‘‘Besides Kiswahili and Gusii, I speak French and German too. I studied French at university before relocating to Germany where I learnt German. I speak these fluently,’’ says Kerubo, who spends her time studying, working in and touring Europe.

‘‘It is important for navigating the world. I can fit in most parts of the world,’’ Kerubo adds.

The introduction of Malay, Russian, Spanish and Italian in some schools, and boosted by the establishment of foreign cultural institutions in Kenya, means Kenyans today have more language options to pick from than at independence. Travelling the world has also allowed Kenyans to acquire new languages.

Hawkers sell their wares in Nairobi in 1980.

We also have more food varieties on our menu today than we had at independence, thanks to the influences of modernity, cultural integration and imitation. While we only ate ugali, chapati, meat and indigenous foods in 1963, today, we have pizza, sushi and other seafood on our plates as traditional foods, namely vegetables, tubers and grains, slowly disappear from the scene. Some dishes such as irio (mixture of mashed potatoes, maize and beans) and matoke have survived the wave of culinary trends to remain a staple among Kenyans.

Our food palate keeps expanding, exploring exotic delicacies and accommodating new ones in our food menu. This explains why Kenya continues to attract international restaurant brands such as Burger King, Subway and KFC that have been expanding their presence in Kenya in recent years.

We may have been consumers of bread, chapati and cake sixty years ago, but Kenyans consumed 13.7 kilos of wheat per person per year, compared to 43 kilos per person today. Back then, most wheat products were considered a luxury with chapati, for instance, only available during Christmas for some families.

Not anymore, with the dish having graduated to a weekly staple as our appetite for wheat strikes an all-time high calibration. The country now consumes about 2.5 million tonnes of wheat every year, the bulk of which is imported.

Drinking nation

We are also drinking more today than we did at the birth of our nation if data from the National Authority for the Campaign against Alcohol and Drugs Abuse (Nacada) is anything to go by. Kenyans consume an average of 4.5 litres of alcohol per year, with 1.2 per cent of them considered binge drinkers, according to a 2014 report by the World Health Organisation (WHO).

Beer is Kenyans’ favourite drink, constituting 56 per cent of all drinks consumed in the country. Little wonder then that Kenyans spent Sh74 billion in 2022 on alcohol brands sold by the East African Breweries Limited (EABL) only. In the region, Ugandans and Rwandans drink more than their Kenyan counterparts at 9.8 litres of alcohol annually. Except traditional brews constitute the bulk of their drink, as statistics show.

Our enthusiasm for meat, though, has been on a gradual decline since independence. In 1963, Kenyans ate an average of 16 kilos of meat per year. Today, we consume 14 kilos, as health consciousness and lifestyles such as veganism take root.

Revellers during the Thriftsocial event held at the Karen Waterfront in Nairobi on February 7, 2021.

‘‘I chose not to eat meat out of health consciousness. It has been three years now. I feel healthier than before,’’ says Spinster Atieno. She admits to eating dairy products, however. To her, the degree of veganism is up to the individual. ‘‘You can choose how much animal products you eat, can’t you?’’

We may eat more today, but we also work out more than we did at Independence. Gym facilities now dot the country as do jogging trails where thousands of Kenyans exercise daily. Staying healthy and in shape is now part of the national psyche, more so among the middle class.

With more muscle, toned and chiselled bodies, the walking style for some Kenyan men has obviously had to change to something of a spring and self-assuredness of manner, with pumped-up chests. ‘‘When you work out and attain the body of your dreams, you gain more confidence. Naturally, the walking style changes,’’ says Martin Mwendwa, who owns an electronics shop in Nairobi. ‘‘It gives you more poise.’’

While the skin colour of the majority of Kenyan men has barely changed since 1963, the lighter a woman is the more attractive she is considered. The streets of Nairobi and other major cities in Kenya teem with women in different shades of skin, from the bleached to the exfoliated and the lightened.

Valued at about Sh100 billion and targeting the ever-bulging middle-class, skin lightening is easily one of the most thriving businesses in Kenya. The reason is compelling and unsurprising. Kenyans like their skin lighter than darker.

From lightening lotions to smoothing creams, gels and skin-brightening surgeries, the cosmetics market in Kenya has it all. The attitude that light skin is more appealing than dark skin is in vogue now as it was at independence. Not even the ban of 131 skin-lightening products by the Kenya Bureau of Statistics last year has slowed down the race for fair skin as the majority of the banned products continue to sell in the market unabated.

Lightness, though, goes beyond beauty. It is also about visibility, especially for some careers. For many years, professions such as anchors on television attracted women with light skin. These dominate the space to date.

At independence, the average Kenyan mother gave birth to eight children. Today, it appears the appeal for large families has diminished, with the fertility rate for women between 15 and 45 years at an all-time low of 3.2 per cent. In the last six years, the fertility rate has been decreasing at an average of 1.4 per cent per year, according to data from the World Bank.

This can be attributed to a number of factors, including the rising cost of living and education for women who choose to delay childbirth to pursue a career. ‘‘I have one son who is seven. I do not intend to have more children,’’ Peris Lelan, a businesswoman. ‘‘My desire is to provide the best care for him.’’

Are we more individualistic than we were six decades ago? Several factors point to the case. Today, most Kenyans spend more time at work than with people close to them. This leaves minimal time for social interactions. ‘‘Unless I share interests with people, I do not see the need to engage them. There are just too many distractions in life today to bother or be bothered by strangers,’’ argues Daniel Kimani, a physician.

‘‘I do not know my neighbours. And why should I?’’ wonders Kimani, adding that the growing individualism among Kenyans is a byproduct of the rise of social classes. ‘‘I hang out with the same people in my profession and those in the same social spaces I belong to.’’