Bitter lives for families after collapse of sugar companies

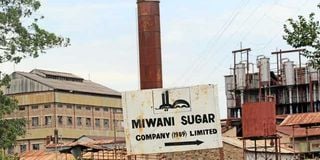

A dilapidated Miwani Sugar Company in Kisumu County in this September 2016 photo. PHOTO | FILE | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- In Busia, Mr Stephen Omuse used to earn Sh1.2 million from his 10-acre land in the good old days.

- Operations at the financially struggling Mumias Sugar in Kakamega and the debt-ridden Nzoia Sugar in Bungoma are limping due to woes linked to poor management.

Thousands of families that depended on sugarcane farming for a livelihood are still contending with the misfortunes brought about by years of mismanagement and plunder of public resources that suffocated the industry.

While the government has expressed commitment to revive the once vibrant sector that provided livelihoods to many in sugar-growing region, many who have since either abandoned the crop or drastically scaled down acreage under farming have adopted a wait-and-see attitude.

In Busia, Mr Stephen Omuse used to earn Sh1.2 million from his 10-acre land in the good old days. A tonne of cane would fetch Sh4,500. But earnings have since dwindled considerably, and the venture is no longer profitable. “We are hoping the promises made by the government to bring reforms in the sector will benefit farmers in the long run,” said Mr Omuse.

Sugarcane farming served as the region’s economic lifeline. But the problems facing the sector have disrupted operations in factories and brought the region’s economy to its knees.

Operations at the financially struggling Mumias Sugar in Kakamega and the debt-ridden Nzoia Sugar in Bungoma are limping due to woes linked to poor management.

Shortage of raw materials

In Kakamega, farmers’ woes worsened after the debt-ridden Mumias Sugar halted sugar milling operations in April 2018.

The management cited shortage of raw materials and said the move was temporary.

Efforts to jumpstart the miller have run in numerous hiccups.

Mr Desterio Okumu, a farmer from Mwitoti in Mumias East, has been forced to reduce acreage under cane from six to one as he diversifies to horticultural and dairy farming. Mr Okumu said the future of the sector is bleak since the government has been making many promises that go unfulfilled.

“Cane farmers are going through tough times to break even in the business, which has become unpredictable because of poor pricing of cane and instability in the sector brought about by lack of regulations,” he said.

He noted that private millers have been enjoying monopoly and frustrating farmers after State-owned factories ran into trouble. “The millers have reduced the price of cane per tonne from Sh4,000 to Sh3,100, and they don’t offer any form of support services to improve the quality of cane,” said Mr Okumu.

Mr Bilal Musa from Lumino in Mumias Central also decided to reduce the cane acreage to one acre from five to cut down on losses . He said unless the issue of debts owed by Mumias Sugar is resolved, promises of the miller being revived will not materialise.

“It is unfortunate that this issue of the challenges facing the sugar sector is always brought up when the next cycle of elections are around the corner. We read mischief in the whole plan since politicians have hijacked the process and are using it as a campaign platform.”

In the Nyando sugar belt, Mr John Okumu pegs his hopes on the scheduled leasing of the pioneering miller to restore the vibrancy of the once sugar rich region. “I scaled down planting of sugarcane to other alternatives like maize and beans after Miwani went under in the early 2000,” he said.

Mr Robert Baraza from Webuye West was forced to uproot sugarcane and diversify to other income generating activities after Nzoia Sugar delayed paying him for many years.

Like other farmers in the Nzoia sugar belt, Mr Baraza now wants the government to involve them in the revival of sugar companies in the region.

In Amukra, Teso South, Mr Stephen Ekirapa is probably one of the major cane farmers, with the crop sitting on a 150-acre farm. But he is staring at losses due to delayed harvesting of mature cane and transportation of the raw material to the factory.

“After harvesting, my cane lies on the farm for over a week before private millers send in tractors to transport it to the factory. The cane is left to dry in the fields and that affects the tonnage, adding to losses.”

He said it was unfortunate that the government had left private sugar millers to dictate what happens in the market, thus subjecting farmers to suffering.

He noted that private millers were exploiting growers during weighing of cane at weighbridges as well as during transportation of the raw material to factories at night.

Reported by Victor Raballa, Benson Amadala, Barnabas Bii and Brian Ojamaa