Anyone still in doubt of the political utility of the ‘system’?

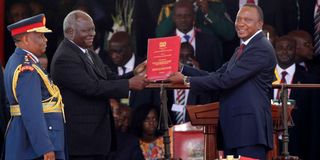

Kenya's President Uhuru Kenyatta (R) receives the national constitution to represent the instrument of his power and authority from his predecessor Mwai Kibaki after his official swearing-in ceremony at Kasarani Stadium in Nairobi on April 9, 2013.

What you need to know:

- Not even the bruising humiliation of the BBI fiasco helped drive the idea home.

- Only Ruto internalised the big lesson: Kenyans relish a showdown with the boastful wielders of state power.

- We are unbwogable; hatupangwingwi. Sovereign power belongs to the people.

Before 2002, the president of Kenya was the decisive variable in our politics.

A literal colossus, he bestrode the land proudly by planting a roughshod foot at each of its poles, with ordinary mortals squirming ineffectually underfoot.

The resources at his disposal were illimitable, and the administrative machinery was at his beck and call on a full-time basis.

Thus, he was omniscient, omnipotent and omnipresent.

Under a presidency whose authority was intentionally fashioned along Europe’s most imperious royal houses, the president was, per the Hobbesian formulation in the Leviathan, a strong temporal approximation of the biblical godhead.

He could reward at whim with endless tracts of land, revoke citizenship, curtail all rights at the stroke of a pen and generally, affect the disposition of all with his slightest act.

Succession plan

In 2002, the retiring president, Daniel Moi, decided to leverage all his unrestrained power in pursuit of the most audacious intervention in his own succession.

Disdaining the formidable phalanx of Kanu grandees, he executed a most outrageous sleight of hand and, like a magician conjuring a rabbit from his hat, whisked out a political toddler to be his successor.

For perspective, Nyayo was a man of his time, a hyper-patriarch who only hung out with the old boys and was big on the elders' thing.

His preferred ally was male, old, and conservative. And his party boasted a galaxy of precisely this type of politician in George Saitoti, Joseph Kamotho, William Ntimama, Kalonzo Musyoka, Nicholas Biwott, Sharif Nassir and Katana Ngala.

Indeed for purposes of the succession suffered from an embarrassment of riches, given the array of highly experienced scions of broad appeal epitomised by Saitoti and Musyoka.

Savvy techniques were employed to determine the best configuration to run the ever-divided opposition out of town.

Raila Odinga urgently mobilised in the background to cash in his handshake and bag the Kanu presidential nomination.

At the last possible minute, Nyayo unveiled Uhuru Kenyatta as his man and commanded all his potentates and the state to escalate him post haste into State House. It did not go well.

At the instigation of an irate Odinga, Saitoti, Kamotho, Ntimama and a host of Kanu die-hards walked off in a huff and joined an opposition outfit, the Liberal Democratic Party, which gave the National Alliance of Kenya (NAK) much-needed impetus to romp comfortably into power as the National Rainbow Alliance (NARC).

As a result, Mwai Kibaki, the grand old man of Kenyan politics, handed young Kenyatta a traumatic political shellacking.

In protesting Moi’s decision so publicly and expressing their ambitions equally vehemently, Saitoti & Co. committed gargantuan transgressions hitherto unimaginable in Nyayo’s Kenya.

In walking out of Kanu in a huff, they infringed another hazardous taboo. Finally, by subsequently not resigning from politics but joining the opposition, these arch-loyalists irreversibly committed themselves to one of the most spectacular apostasies of Kenyan politics.

That they were vindicated by a handy victory obviously goes a long way in assuaging the gnawing question: why, and how could they?

Rebellion

Certainty of electoral victory does not sufficiently explain a rebellion of such breathtaking magnitude.

A better account of the key motive of the revolt that pulverised Kanu is that the system veterans implicated in the mutiny were intimately acquainted with the dimensions of the machinery of the Nyayo state, and familiar with its potency as well as its deficiencies and limits.

The timing of their move also did not give the state time to recalibrate, and in any case, atrophy inherent in the system of an outgoing administration was eating away at the levers and cogs of the thing.

Finally, they had accurately profiled the national mood: Kenyans were loudly expressing a keen appetite for “the system”.

“We are unbwogable!” was the impudent defiance that succinctly evinced this national sentiment.

In 2005, a resurgent Narc state arrogantly hijacked the constitutional review process and brought a controversial draft constitution to a referendum, boasting that it would mobilise a campaign that would “shake every corner of the republic”.

The system accordingly rallied but was ultimately no match for the spurned LDP faction that had found a common cause with a Kanu smarting from devastating political injury.

Never mind that the same LDP was a major cause of its misery. This became the ‘orange’ or the opposing campaign in the ensuing contest.

The government was buried in the plebiscite, and the slippery slope to 2007 commenced in earnest.

Kenyatta, Odinga and William Ruto have been central players in each of these events, yet it is now clear that the lessons of two epic debacles did nothing to temper Kenyatta and Odinga’s faith in the power of “the system”.

Not even the bruising humiliation of the BBI fiasco helped drive the idea home.

Only Ruto internalised the big lesson: Kenyans relish a showdown with the boastful wielders of state power, especially when the administrative system and public finances are abused.

We are unbwogable; hatupangwingwi. Sovereign power belongs to the people.

Mr Ng’eno is a lawyer and former State House speechwriter.