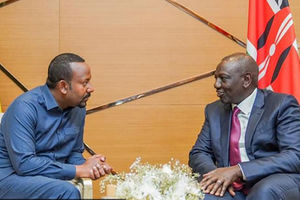

President William Ruto receives the Prime Minister of Ethiopia, Abiy Ahmed, at the Jomo Kenyatta International Airport, Nairobi on February 27, 2024.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed is arriving in Kenya on Tuesday night, according to a tentative programme, for his first State Visit since June 2018.

And one running thread, whenever Kenya and Ethiopia officials meet is the way they refer to their “historical foundation” on which their ties run.

When Abiy last came on a state visit, a communique said both he and then President Uhuru Kenyatta had “agreed that the vision of the forefathers points to a future of shared values, culture and tradition.”

So how does Abiy’s coming matter to Kenya? Besides sharing the border, Ethiopia was also the first African country to establish diplomatic relations with Kenya in 1963. The friendship that existed at the time led to both countries allocating land for embassies to be situated close to their respective national palaces, lifting any visa requirements for their nationals and entering a mutual security pact. They also have a Special Status Agreement which seeks to establish relations between them focusing on the special needs of either side.

Security needs

That mutual pact reflected the challenges they faced then. But which has endured. In 2018, they identified cross-border security challenges, “exacerbated by vulnerable communities, as obstacles to sustainable peace.” The two sides pledged to focus on promoting inclusive economic growth in the border regions. Ethiopia has since endured its own local security challenges after violence erupted in the Tigray region and later militia emerged in other areas like Amhara.

President William Ruto (right) receives the Prime Minister of Ethiopia, Abiy Ahmed Ali, at Jomo Kenyatta International Airport, Nairobi on 27 February 2024. PCS

Last week, the Joint Ministerial Commission (JMC), Kenya’s oldest bilateral organ with a foreign country, established in 1963 referred to the same issue of security along their common border. But both countries continually face the threat of violent extremism which requires adequate cooperation. Last month, their intelligence agencies agreed to continue sharing information on common threats, especially in the wake of the conflict in the Middle East that is spilling into the Red Sea.

Economic needs

This time, the trip is punctuated by security and economic undercurrents, which means both issues are interlinked. For example, Ethiopia’s need to access the sea is both an economic opportunity for Kenya and a potential spark for a security problem. In January, Ethiopia and Somaliland touched off a spark with Somalia after signing an MoU to access the sea. Somalia considers Somaliland its territory.

Abiy’s trip is coming at a time when Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud was also scheduled to travel to Nairobi to attend the UN Environmental Assembly meeting. Aides on both sides have refused to confirm the possibility of any dialogue while in Nairobi.

Yet that tiff could benefit Kenya though, which is seeking to attract users to Lamu Port, a new facility recently built by the Chinese.

In 2018, Kenya and Ethiopia said they were reviving the Lamu Port South Sudan transport corridor (Lapsset) which had been near-dead since the launch in 2012. Kenya has since completed the Port. In 2018, it had pledged to “facilitate the formal acquisition of land in Lamu Port given to the Ethiopian government and the Ethiopian side reiterated its commitment to develop the land for logistical facilitation.”

Ethiopia’s buy-in was mostly delayed by Covid-19, and its own internal political problems. But the area of interest has also been vulnerable to violent extremists. This visit could review the promise the two sides made in 2018: to “jointly supervise and inspect the Lamu-Garissa-Isiolo-Moyale and Moyale-Hawassa-Addis Ababa road networks.”

At the JMC last week, foreign ministers from the two sides said they will also work on Non-Tariff Barriers (NTBs) that have impeded the full use of the Lapsset transport corridor, the dispatch said. Some of those include irregular security and poor infrastructure.

In 2020, they opened a One-Stop-Border Post in Moyale. But has been mainly idle. One reason is their currencies are not exchangeable directly, meaning they need the dollar to do their business. It has become a barrier in itself.

The two sides agreed last week they would work on “removing unnecessary checkpoints, harmonising axle loads between the two countries, harmonising customs protocol and systems” as well as strengthening the Moyale One-Stop Border Post.

Integration and its politics

Kenya has often traded better with Uganda and Tanzania than Ethiopia, due to the former two belonging to the East African Community where the trading rules are somewhat easier. But the EAC market is not always smooth, as seen in the regular disputes with Uganda, and Tanzania. The solution? You have to keep expanding alternatives.

Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed signs a visitor's book after arriving in Kenya on February 27, 2024, as President William Ruto looks on.

Which makes Ethiopia attractive. In February, Ethiopia’s Minister of Transport and Logistics Alemu Sime indicated they may consider importing agricultural shipments through Kenya's Lamu port, in a move to diversify its trade routes and reduce heavy reliance on ports in Djibouti.

Mr Sime told Parliament that Ethiopia is eyeing the Kenyan port for trade activities, including exporting livestock and other farm inputs through the Southern border.

Three weeks ago, the first Lapsset Corridor Development Programme Joint Technical Committee meeting, in partnership with the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) and the NEPAD/APRM Kenya, agreed on governance structures meant to guide the ambitious project.

Abdulber Shemsu, the CEO of the Ethiopian Maritime Authority spoke candidly about Lapsset: “The Lapsset initiative presents evidence of Ethiopia’s commitment to utilising multiple transportation avenues to foster connectivity and promote economic development in the region.”

Not that Kenya can afford to discard EAC. In fact, President Ruto and opposition leader Raila Odinga toured Kampala on Monday to try and sort out the ongoing dispute over oil imports through Kenya.

Uganda had opted to use the port in Tanga, Tanzania and had sued Kenya at the East African Court of Justice. For now, Kenya knows the dispute is not long-lasting and has a better offer over Tanzania on distance and efficiency.

But Nairobi also knows that EAC should keep expanding to dilute centres of disputes and provide alternatives. This is why Somalia’s entry into the EAC is important and has courted Ethiopia to start applying to join.

Geopolitics

President Ruto and Abiy have in the past year looked like rivals on the international stage. While internal problems seemed to distract Abiy from looking inward, Ruto has taken vocal positions including climate change and reforming international systems. Yet they need not battle abroad. For a long time, the two sides looked like the most stable go-to countries to help quell chaos in the Horn of Africa, especially in Somalia and South Sudan.

Now they have seemed to pursue divergent goals. Ruto seems to be the darling of the West and Abiy is shining in China, as seen during the last Belt and Road Initiative when he spoke on behalf of Africa in Beijing, in October. Ethiopia has also formally joined the BRICS bloc

Of course, Addis Ababa is the African diplomatic capital and Nairobi is the only headquarters of the UN outside of the Northern Hemisphere; which means they will always be in focus by all the big players